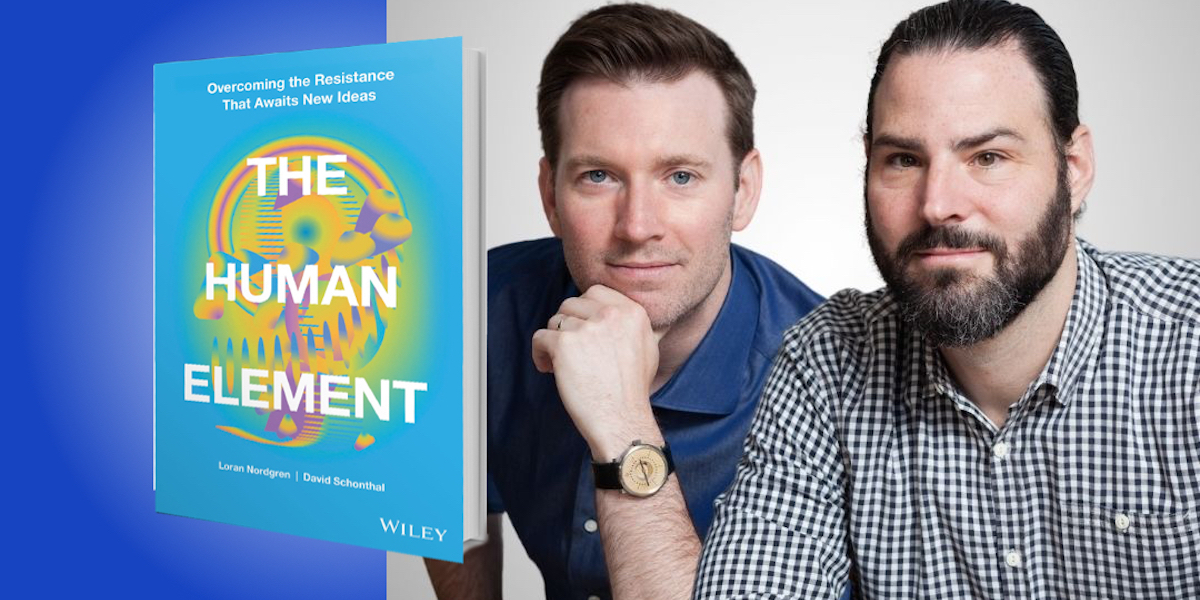

Loran Nordgren (an organizational psychologist) and David Schonthal (a venture capitalist) are both professors at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. They wrote The Human Element as a resource for innovators who want to get their ideas to lift off, and then stay in flight, by looking beyond the hype and curbside appeal of their pitch, and into the details of why enticing offers and products often become crashed failures. Read 5 key insights from the book below, or listen to the audio version—read by Loran and David themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We think in Fuel.

When a bullet is fired from a gun, it leaves the barrel traveling 1,300 feet per second, breaking the sound barrier. If shot at the ideal angle, it can travel for nearly two miles. In a steady hand, a bullet will strike its target with pinpoint accuracy, time and again. What enables such a technologically simple device to achieve such extraordinary power and precision?

Most people’s answer is gunpowder. When gunpowder ignites, it creates enormous pressure inside the barrel of the gun, and the only way for the gas to escape is to push the bullet out through the end of the barrel. Gunpowder, therefore, isn’t the wrong answer—it’s just woefully incomplete.

When an object takes flight, two opposing forces are at play. There are propelling forces that thrust the object forward, such as gunpowder or a jet engine. And then there are constraining forces that push back, like gravity and wind resistance. For a bullet, the biggest obstacle to flight is drag. That’s because the faster an object moves, the more drag it encounters. The reason a bullet can fly with pinpoint precision over great distances is because it is aerodynamic, having been optimized to reduce the friction operating against it.

Similarly, when you launch a new idea, two opposing forces are at play. There are forces that propel the idea, which we call Fuel. Fuel is anything that makes an idea more attractive and compelling. Fuel covers everything from the features and benefits to the way that it is communicated. The job of Fuel is to ignite our desire for change, but there are forces that oppose change, which we call Frictions. We may not see them, but they are there, quietly acting as drag on innovation.

“By focusing on Fuel to enhance attraction, innovators neglect the other half of the equation—the Friction that works against the change.”

Most people operate on a deep assumption that the best way to sell an idea is to heighten the appeal, to add Fuel. We instinctively believe that if we add enough value, people will say “yes.” And if people reject our offer, we believe it is because there’s insufficient Fuel. We call this a “Fuel-based mindset.”

But by focusing on Fuel to enhance attraction, innovators neglect the other half of the equation—the Friction that works against the change. Ignoring Friction is like building an airplane without taking aerodynamics into account, and only thinking about the power of the engines. This is precisely what we do when we launch a new idea or initiative, so it’s no wonder that so few take flight.

2. Why we think in Fuel.

One day we got a call from a company in search of help. The company is a fast-growing startup that is redefining how furniture is sold by allowing customers to create a one-of-a-kind, fully customized sofa at a price about 75% cheaper than other custom furniture companies. Customers love spending hours on the site or working with a design specialist creating a sofa that is perfect for them. But something mysterious happens right before would-be customers hit the “order” button: nothing. They disappear before completing their purchase.

The company’s instinct was that some aspect of their product must be driving them away. Maybe prices are too high, or they need to add more options, or elevate the in-store experience. But it turns out that the problem had nothing to do with the company’s appeal. There was a Friction standing in the way: People didn’t know what to do with their old sofa! Will the garbage truck take it? If not, who will? Until they resolve this, people can’t move forward with their purchase.

As this example illustrates, humans have a funny habit of explaining behavior in terms of internal forces like motivation and intent, and downplaying situational forces. Psychologists call this the fundamental attribution error. And it is a nearly unbreakable habit of the mind.

“Humans have a funny habit of explaining behavior in terms of internal forces like motivation and intent, and downplaying situational forces.”

Fuel reinforces our attributional tendencies. Fuel is designed to stoke motivation and intent. Why aren’t people buying your product or proposal? “They must not find it exciting,” we imagine. If that’s the reason your mind constructs, then the way you change that behavior is to increase excitement by adding Fuel. That is why we fixate on Fuel.

3. The limitations of Fuel-based mindset.

A doctor says, “I have good news and bad news; which do you want to hear first?” What would you say? A majority of people pick the bad news. This is because, for the human mind, bad is stronger than good. If you’ve ever gone through a performance review, you’ll know what we are talking about. One negative comment can instantly wash away all the positive observations that preceded it. Psychologists call this the negativity bias.

Our bias for bad affects how we see almost everything. We remember negative events more intensely than positive events. We process negative information faster than positive information. A threatening image can trigger our fight-or-flight response in milliseconds, but positive events produce much slower reactions. You jump back from a snake much faster than you jump toward your favorite snack.

When people hesitate to embrace a new idea, there are two broad explanations. Either the idea lacks appeal (insufficient Fuel), or a Friction is blocking progress. Negativity bias has a clear implication: Focus on the Frictions. This shift in mindset can be seen in Bob Sutton’s wonderful book, The No Asshole Rule, which tackles a problem that plagues many companies: low workplace morale. The conventional response to a disengaged workforce is to add benefits, to crank up the positive in hopes of drowning out the bad. What Sutton proposes instead is fearless intolerance for bad people and bad behavior. The negativity bias leads to the realization that benefits and perks will rarely overcome a toxic culture.

“When people hesitate to embrace a new idea, there are two broad explanations. Either the idea lacks appeal (insufficient Fuel), or a Friction is blocking progress.”

The parallels with innovation are striking. When we sell an idea, our focus is on the benefits the idea offers. We implicitly ask ourselves, “How will we seduce them into saying yes?” And when our message is ignored or outright rejected, our response is to crank up the perks. Fuel is important, but Fuel isn’t the mind’s first priority.

4. Friction is a source of untapped opportunity.

Because people fixate on Fuel, it has become an over-exploited resource. There can be incredible opportunity in spotting the Frictions that your competitors have failed to resolve. Consider the success of the dating app, Tinder. Before Tinder, online dating was dominated by companies like Match.com and eHarmony. These companies require you to build a detailed profile of yourself, including intimate details like political views, salary, and body type. Next you search the huge database for potential matches. Then, once you find someone you like, the final step is to send them a perfectly crafted email.

But expressing interest in someone takes courage because you are making yourself vulnerable to rejection. Imagine finding a potential date who seems a perfect match. You send them a thoughtful message, but for a Match.com user, you often hear things like: “I’m looking for someone a little younger.” “Sorry, I don’t date Republicans!” “You’re not my type.”

Or perhaps worst of all, you don’t hear anything at all. The point is that traditional online dating produces a lot of rejection, and many people drop off these sites because they find it difficult to bear. Tinder greased the emotional Friction of online dating by creating a system based on mutual interest. To have the ability to reach out to someone on Tinder, both people have to “swipe right” on each other. Mutual interest is established before people make themselves vulnerable. Tinder’s core insight was that you feel more comfortable approaching somebody if you know they want you to approach them. Spotting and fixing the pain helped Tinder transform the dominant model for online dating.

“Tinder’s core insight was that you feel more comfortable approaching somebody if you know they want you to approach them.”

5. Finding Frictions requires empathy.

Despite their power and importance, Frictions are easily overlooked. Consider the following thought experiment: Imagine you run a non-profit that gives social support to children in hospitals. Your organization encourages people to write and send “hero cards”—letters of support to hospitalized children. How would you increase participation in this program?

When we posed this question to a group of people, two suggestions came up again and again: Explain how the cards help children, and incentivize people for writing them. We tested these influence intuitions, along with one of our own. One group received quotes from children explaining how much the cards meant to them. Other people were paid a small amount for each card they wrote. And for a final group, we simply made it easier to write a hero card by giving them templates. The first two interventions barely moved the needle, but when we gave people templates, responses rose significantly.

What made the template approach so effective? Does anyone think supporting sick children is unimportant? Of course not! They weren’t resisting because they didn’t think it was worthy; they were reluctant because they didn’t know what to write. They struggled with questions like: What’s appropriate? What words should I use? Should the message be happy or sympathetic? That uncertainty was a Friction that defused the tactics designed to Fuel change. Giving people templates removed the Friction, and behavior changed.

Frictions are difficult to spot because they require empathy. They require that you see the world from the perspective of your audience. When you are selling change, it’s natural to fixate on the idea. But to understand Friction, you need to shift the spotlight from the idea to the audience.

To listen to the audio version read by Loran Nordgren and David Schonthal, download the Next Big Idea App today: