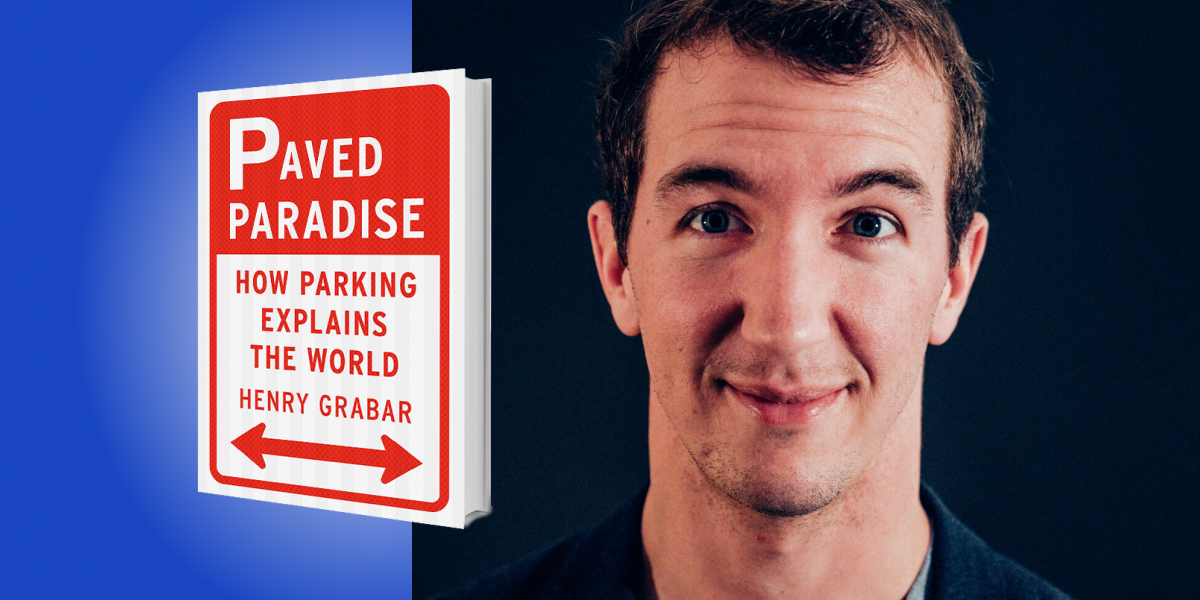

Henry Grabar is a staff writer at Slate who writes about housing, transportation, and urban policy. He has contributed to The Atlantic, The Guardian, and The Wall Street Journal. He received the Richard Rogers Fellowship from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and was a finalist for the Livingston Award for excellence in national reporting by journalists under thirty-five.

Below, Henry shares five key insights from his new book, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World. Listen to the audio version—read by Henry himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There is a LOT of parking in this country.

There are between four and nine parking spots for each car. There is more parking per car than there is housing per person. In Los Angeles County alone there are 19 million parking spots, or 14 percent of incorporated land in the county. That’s more land than the moving lanes on the streets and the freeways put together! In Silicon Valley, the wealthiest region of the United States, parking is 13 percent of the land. There are 15 million parking spots in the Bay Area, enough to wrap a parking lane around the earth. Twice.

The smaller the city, the more parking there is. Seattle has five parking spaces per household. Des Moines, Iowa has 20 per household! Parking makes up 28 percent of land in Louisville and 29 percent of downtown Kansas City, even if you exclude garages inside or underneath buildings, and you don’t count curb parking!

In the mid-aughts, when the team of programmers at Maxis were working on the first new SimCity game in a decade, they studied American municipal architecture, politics, and urban design to try and produce a compelling simulacrum. Lead designer Stone Librande used Google Earth to measure his surroundings. The biggest surprise he found was the size of the parking lots. “When I started measuring out our local grocery store, which I don’t think of as being that big, I was blown away by how much more space was parking lot rather than actual store,” he said. “That was kind of a problem because we were originally just going to model real cities, but we quickly realized there were way too many parking lots in the real world and that our game was going to be really boring if it was proportional in terms of parking lots.” In the game, he said, they tried to imagine that the parking was underground: “We had to do the best we could do and still make the game look attractive.”

2. Ample parking has costs.

Worse still, in most jurisdictions, all this parking is required by law. Every restaurant, office, pool hall, library, courthouse, laundromat, and so on must come with a precise number of parking spaces. Most importantly, every new house or apartment must come with a set number of parking spaces as well.

These zoning laws have had huge consequences. They make it impossible to reuse old buildings, compelling teardowns. For a century, American architecture has evolved in tandem with parking laws, as increasing quantities of required parking have forced developers to move from the early 20th-century vernacular—corner taverns, storefront groceries, row houses, three-flats, triple deckers, and bungalow courts—to fast food chains, big box stores, and houses whose primary architectural feature is the garage door.

“Parking has created an urban landscape so divided by lots that it is difficult or dangerous to use transit, walk, or ride a bicycle.”

All this required parking has had huge effects on transportation, functioning as an enormous subsidy for car ownership. Parking has created an urban landscape so divided by lots that it is difficult or dangerous to use transit, walk, or ride a bicycle. Parking minimums are like some mutant strain of yeast in the city dough, inflating and expanding architecture and urbanism with bubbles of asphalt.

And the more we drive, the more parking we crave. In the early days, certainly, parking facilities arose in response to demand. But later, thwarting the hopes of the planners who decided to require parking in every new building, they began to create it. Research has shown that parking growth between 1960 and 1980 was a “powerful predictor” of car use in the following two decades. In other words, more parking appeared to cause more driving, not the other way around.

Finally, these parking mandates are of course terrible for the environment, since they pave so much land. That changes the way cities interact with rainfall, heat, and wildlife.

3. Parking has a literal cost, too.

You don’t pay for parking when you park, most of the time, but someone does—a little bit of every bar tab, grocery bill, and most importantly, your rent or mortgage payment, is going toward paying for parking.

It might seem like the easiest thing in the world to build, but parking is actually pretty expensive. Surface parking costs a few thousand dollars a stall, not including the land it takes up. Garage parking costs tens of thousands of dollars a stall. Underground parking can run you into the six figures, per space!

Multiply those figures by all the parking we’ve built, and you come to an astonishing conclusion: Our parking stock is probably worth more than all our cars put together.

“Even if you don’t have a car, you pay for parking anyway.”

To no surprise, this has tacked on a massive expense to everything we build, especially housing. Required parking adds tens of thousands of dollars to the cost of low-income apartments. It raises big-city rents by double-digit percentages. Even if you don’t have a car, you pay for parking anyway.

It’s impossible to understate how much this changes the kinds of things we can build. When Seattle recently decided to stop requiring developers to include parking in new homes near transit, the results were intriguing. Most developers still built parking. But they build a lot less than they used to. Over just six years, they built 60,000 fewer parking spaces—lowering the cost to build those new apartment buildings by half a billion dollars!

4. Free street parking is a disaster.

Why do we have these crazy rules? Because we’ve neglected to manage one of a city’s most valuable resources: The curb.

When you make something popular free, you will soon run out of it. This happens every day where curb parking is free in busy neighborhoods. Employees show up first thing in the morning, take all the best spots, and park all day. Customers who come later to eat a meal or run an errand find there’s nothing left. Pretty soon, free parking for me has become a parking shortage for thee. Then comes double parking, parking tickets, traffic jams, and lost time. The worst consequence happens when customers take their business to malls with ample parking in the suburbs.

How much downtown traffic is created by looking for parking? About a third. That’s a lot of driving! Consider data from Westwood Village, a commercial neighborhood in Los Angeles. It only took drivers three minutes to find parking. But multiply by the hundreds of people coming and going every hour, it added up to 35 hours of cruising for parking every hour! The average hunt distance was a half mile. This single neighborhood, with its 15 blocks of 470 underpriced parking meters, was generating 3,600 extra miles of driving every single day.

When people don’t easily find parking, they fight about it. Dozens of people are killed in parking space murders every year.

Properly price curb parking, on the other hand, and it becomes possible to find a space where you want it, when you want it. When San Francisco started charging more for curb parking on its busiest streets a few years ago, parking citations actually went down. Maybe because it was easier to park. Or maybe because people thought they were getting something worth paying for.

5. There are people who are obsessed with parking.

The picture painted so far is pretty grim. There’s a whole movement of people trying to fix this state of affairs. They call themselves Shoupistas, after Don Shoup, a professor at UCLA whose research on parking started a movement.

The Shoupistas are designers, environmentalists, developers, planners, pedestrians, small-business owners, restaurateurs, and food trucks. They are also start-up founders doing e-commerce and hippies riding bicycles. They are people who don’t drive or don’t want to.

They come from the Left, frustrated by a hidden nationwide subsidy for fossil fuels and enraged by the hurdles to building low-income housing. If they come from the Right, their ideals are thwarted by laws that tell you what to do with your property with dubious justification.

“Driving may feel like freedom, but our inability to get around any other way is a kind of prison.”

Shoupistas are also preservationists who wish to see old buildings find a second life, as well as anti-preservationists who want to see new buildings everywhere. These people also include free marketeers who want dynamic parking pricing, as well as good-government advocates who want revenue for public improvements. Their slogans can be “yes in my backyard” YIMBY if they are pro-housing activists. But these groups also include small-city restorationists of the Strong Towns movement. Finally, Shoupistas can be architects who subscribe to Congress for New Urbanism.

Shoupistas have solutions to make our American parking situation better. This is the story of how we destroyed our cities in search of parking, and the people who helped make it so: the mall builders and mobsters, the police, politicians, garage magnates, and community groups. But it is also a chronicle of those who have begun to repair the damage, waging an unpopular war to take parking down a notch on America’s hierarchy of needs, and restore the space it took from us. (Not all the way down, mind you.)

I’ve read more books about car culture than I care to count, and I’m continually struck by how poorly they have aged. Their disdain for the suburbs and the people who live there is condescending at best and, in light of today’s urban real estate prices, newly classist. I come to bury that rhetoric, not to praise it. I propose an honest reckoning with the externalities of cars, but it is not anti-car. Parking has made an awful mess of the American city, but drivers are not the architects of this system. In a way, they are its victims. Driving may feel like freedom, but our inability to get around any other way is a kind of prison.

A first principle when approaching this issue is acknowledging that most people would like to be able to leave the car behind once in a while—to travel on foot, on a bike, with a kid on Rollerblades or a baby in a stroller, on a bus that comes when you need it and goes somewhere you want to be.

To listen to the audio version read by author Henry Grabar, download the Next Big Idea App today: