READ ON TO DISCOVER:

- Why Susan Cain quit her job as a Wall Street attorney

- Why creativity and financial pressure don’t mix

- How introverts can thrive at any networking event

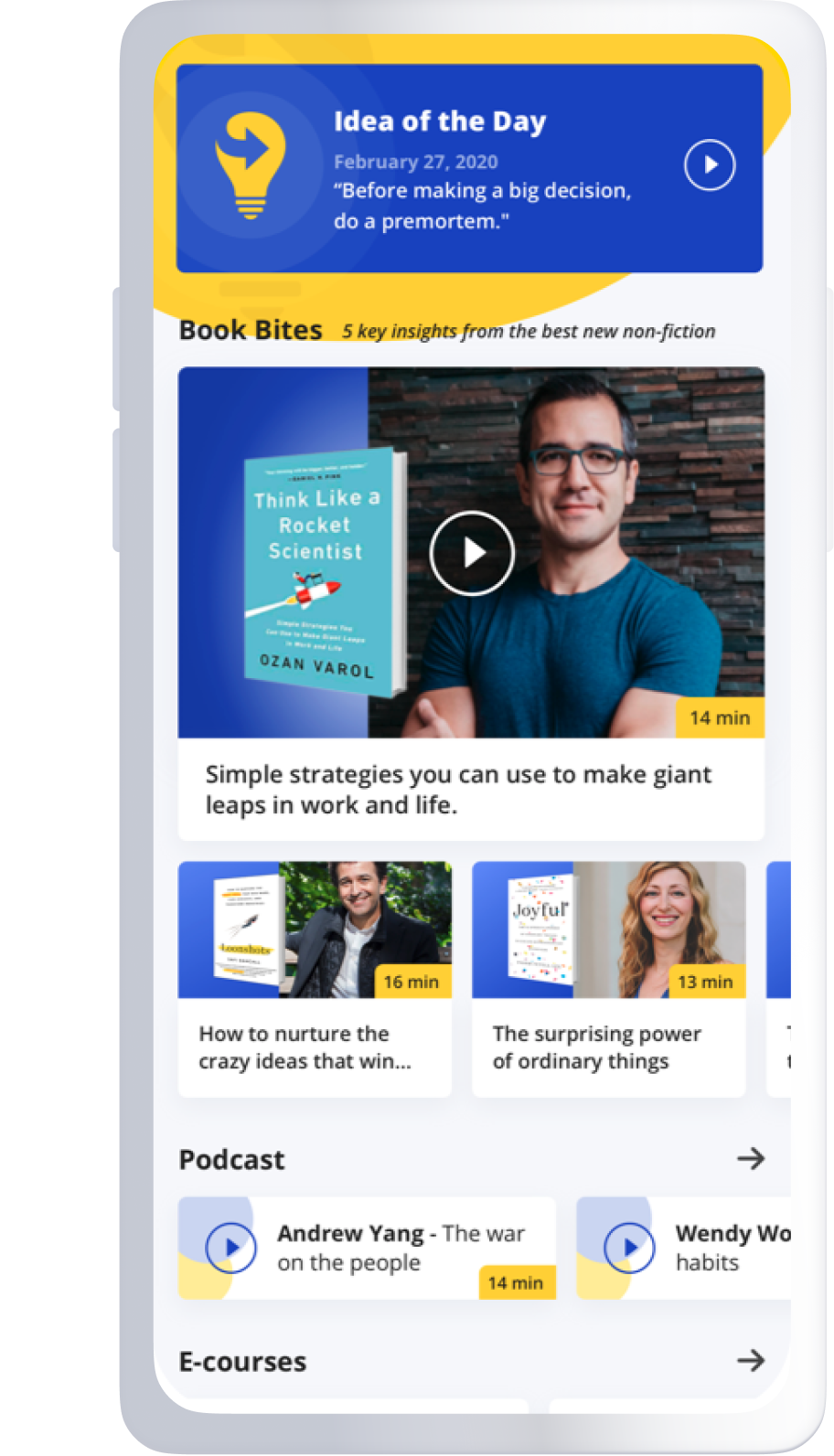

Susan Cain is the author of the world-renowned Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. Her record-breaking TED Talk has been viewed tens of millions of times, and she is a curator of the Next Big Idea Club. She recently sat down with law professor Ozan Varol on the Famous Failures podcast to discuss her journey to becoming a writer, and how she avoids small talk in favor of real, rewarding conversations.

This conversation has been edited and condensed. To listen to the full version, click here.

Ozan: You worked for seven years as an attorney on Wall Street before deciding that a legal career wasn’t for you. What prompted you to reach that conclusion?

Susan: I had wanted to be a writer since I was four years old, and had completely forgotten about that dream during the time that I was a lawyer. But the whole time that I was practicing, I felt like an imposter—not because of imposter syndrome, but because it really was not the right profession for me. My colleagues were really excited if they were working on a transaction that was on the front page of the Wall Street Journal, and I didn’t care about that at all.

I had a turning point when I came across this book called Do What You Are, which helped you take the Myers-Briggs personality test, and then use that information to think about the right career for you. I took the test, and I was an INFP. When I turned to the careers for that type, they were writer, social worker, psychologist, clergy person—this constellation of careers that immediately felt like, “Oh yeah, that’s me.” But they did not resemble what I was doing at the time.

A few years after that, one of the senior partners in my firm came into my office one day and said that I was not going to be put up for partner that year, as I had expected. I was crestfallen and embarrassed and liberated all at once. About an hour later, I asked if I could take a leave of absence. I left the firm that afternoon, and I never practiced law again.

Ozan: You said that you felt your chosen career wasn’t the right one for you, but you still stuck it out for a while. It seems that we tend to build up our significance or identity around what we’re doing. So we tell ourselves a story: “I’m a serious lawyer, and serious lawyers don’t give up a high-power legal career to go become a writer.” Once you tell that story to yourself enough times, even if you feel like there’s something wrong, it becomes really hard to risk your significance by pivoting away from what you’re doing.

Trending: How to Transform Daily Habits into Life-Changing Rituals

Susan: Yeah, I think there is that story that you have of yourself, and it’s not clear what the alternative story, the alternative pathway, is going to be. So it’s not only that you’re giving up a specific professional identity—you’re giving up any professional identity. I remember the feeling of being in freefall after [quitting], and that can be scary. And all the time, and energy, and financial investment, and professional networking that you’ve invested into career path feel like they’re for nothing, and that’s really hard.

When I met my husband—I think it was our second date or third date—we had tickets to see a movie, but we were at a bar, and we were having a good time, and we would have had to leave prematurely to go see the movie. I was getting ready to go and he said, “No, it’s a sunk cost. We already paid for the tickets, but let’s just stay here, where we’re having a good time.” I loved that, and that whole approach to life. If you’ve invested time in A, but A isn’t the right path, forget it—figure out something different.

“If you’ve invested time in A, but A isn’t the right path, forget it—figure out something different.”

Once I was on leave of absence, I wasn’t thinking that I was going to be a writer—I just thought that I was going to travel and hang out. But within a few days, I found myself signing up for a class in creative nonfiction writing at NYU. And when I showed up at that class, I felt like I had arrived at where I was truly supposed to be.

But I never in my wildest dreams expected to earn a living from writing, so the first thing I did was figure out, “Okay, how can I organize my life around writing, but have my income come from somewhere else?” I started a little consultancy, teaching people negotiation skills that I had learned during my legal career. That was something I could do in a freelance way in the evenings, and then I could write during the day.

When making big changes, I’m a big believer in having a backup plan, a financial cushion—especially if you’re leaving to do something creative. I don’t think that creative projects work when you’re really stressed about paying the rent. You want to have as much emotional freedom around your creative projects as possible, and that’s only possible once you’ve figured out what the financial cushion is going to be.

In fact, during that time I also went to this class for people who aspired to be freelance writers. I went to the class full of hope, but I actually hated it, because making a living from freelance writing seemed like a life of constant hustling and stress. This was before I started to write Quiet, and I was just writing all kinds of different stuff. I wrote a play, and a memoir, and stories, but I never tried to publish any of it—it was all just a big, fun thing that I was doing. It was really important for me to start that way, with no financial or professional pressure around it.

Ozan: Even after success comes, many creatives tend to not make their writing their only source of income, because when you’re under that financial pressure, it’s really hard to be creative. Soman Chainani, the author of The School for Good and Evil—which is going to be a major motion picture soon—still does tutoring for high school students on the side. He says, “It’s the only way I know how to write without feeling like it’s a matter of [economic] life and death.”

How did you come up with the urge to write about introversion?

Susan: It was a story I had been living all my life—I’d been thinking about it in one way or another since I was very small. When I first started working on it, I hoped to make a book out of it, but I had no idea it was going to become this gigantic thing. It felt much more like an idiosyncratic, personal project.

“I’m a big believer in having a backup plan, a financial cushion—especially if you’re leaving to do something creative.”

I had taken that creative nonfiction class, and a bunch of us from the class stayed together for some years in a writers group. When I got the idea for the introversion book, one of the members of my writers group was a publishing lawyer, and she knew a book agent named Richard Pine.

So I put the book proposal together and sent it to Richard and four other agents. The other four came back with responses like, “Well, I like the writing, but this idea is not very commercial—could you come back with another topic?” Richard was the only one who instantly got it. And that is a lesson that has stayed with me for the rest of my life—all of these agents were at the top of their field with really good judgment and great track records, but none of that mattered. Because this stuff is subjective, it’s a matter of finding the right person for any given project, and not taking the no’s too seriously along the way.

Ozan: I’m an introvert, and I remember reading the book in the summer of 2012. I was at this big conference for law professors, and there were hundreds of people there—an introvert’s nightmare. So I was trying to network and shmooze, but I’m terrible at small talk, and every conversation I have was exhausting. So every hour I would either run into the restroom to take a breath, or I would go up to my room and read your book. It spoke to me because for the vast majority of my life, I thought there was something wrong with me—I didn’t think of myself as witty or a good conversationalist. So reading your book, especially in the midst of this conference that was designed for extroverted people, was such a godsend.

Trending: 5 Reasons Life Gets Better After Your 40s

Ironically, writing about introversion put you into the spotlight. The book became a huge success, and you gave a TED Talk that became one of the most-viewed TED Talks of all time. As an introvert, how do you balance the demands of publicity with your need to be alone?

Susan: It’s funny, because I used to be flat-out terrified by speaking, and now I’m quite comfortable with it. I go around speaking to companies and organizations and conferences about how to harness the talents of their introverts, and how to help introverted and extroverted teams work well together.

People will often say to me, “Well now that you’re doing that, you have obviously turned into an extrovert.” I’m like, “No.” All of us—introverts and extroverts—are acquiring new skills all the time, and you layer those new skills on top of your personality. It might end up looking like a different picture, but the underlying person is still the same. I am out in public quite a bit, but I still have a lot of alone time and quiet time with people I love. My typical day is still getting up and exercising and writing, and then maybe doing an interview or two, picking up my kids from school, and then hanging out with my family.

“All of us—introverts and extroverts—are acquiring new skills all the time, and you layer those new skills on top of your personality. It might end up looking like a different picture, but the underlying person is still the same.”

Ozan: Do you have any advice for introverts who find themselves in a conference or networking event? These conferences tend to be set up for extroverts, so in a setting like that, how can an introvert thrive?

Susan: I would actually look for ways to put yourself forward and maybe give a short talk or two. Public speaking has such a disproportionate bang for the buck in terms of your career visibility—there’s something about being at the front of the room that causes everybody to start thinking of you as having more authority than before. And it’s actually a lot easier to navigate a conference if you’ve been a speaker, because now everyone knows who you are, and you’ve got something to talk to them about.

If you’re just showing up at a conference, I always think of my goal as finding a few kindred spirits among my fellow attendees. Once I’ve met a few of those kindred spirits, then I feel like my job is done, and I can go up to my hotel room and read a book. Then you keep in touch with those people, and if you do that enough times, you’ve suddenly got an amazing network.

So go out there and ask people questions, questions that are designed to get to who they really are. Not like, “What do you do for your company?” But more like, “What do you love to do? What do you enjoy most in life? What are your favorite things to do on the weekend?” Questions like that will get people going, and from there you can figure out who the kindred spirits are, and really try to nurture those connections. So if you’re not the person who loves working the entire room, I think it’s helpful to not think of that as being the goal. There are other ways to find success.

Ozan: I love that list of strategies, and if I could add one more—don’t be afraid to leave the room and take a quick break in the restroom, just to take a breath and maybe splash some water on your face. I find that really refreshing, because the moment I’m thrust into a group setting where small talk is the norm, I become exhausted very quickly. So give yourself permission to just step outside, get some fresh air, or go into the restroom or up to your room for five minutes. It goes a long way.

Susan: That is such good advice. I can’t tell you how many people [have told me they] feel the way you just described, and are using the strategies that you just described.

“Go out there and ask people questions, questions that are designed to get to who they really are.”

I think the reason group settings [can be so] exhausting is that there’s this strange norm about group conversation that you’re not supposed to talk about anything real. I don’t know why that is, because I think everybody wants to talk about something real. In groups, [the norm] is either small talk, or telling a witty anecdote about something that happened to you last weekend—but you don’t really dig into the meat of things.

Ozan: Yeah, absolutely. I want to cut through the talk about the weather and really get to know each other—and show vulnerability, too. If people are holding up their guard, it’s hard to dig deeper. But I think that’s how friendships deepen—moving beyond the conversations that tend to dominate group discussions, and get to those deeper subjects that people don’t often speak about.

Trending: 5 Simple Strategies for Persuading Anybody

I wanted to ask you one last question: How long did it take you to write Quiet?

Susan: It took seven years. I didn’t really know what I was doing, because I had never published a word in my life. About two years into my contact, I gave a first draft of the book to my editor and she said, “This is terrible. Go back and start from scratch.” You might think I would have been really upset by that pronouncement, but I was actually thrilled, because I knew that it was terrible. My biggest fear was that she was going to hold me to the delivery date in the contract, and that I’d have to go out in public with this terrible thing. So I was thrilled that she gave me all the time I needed to make it good.

Richard, my agent, also gave me that same candid feedback. You really need people who give you that feedback, because I had another editor at the time who was like, “Oh yeah, this is fine—let’s keep publishing this.”

Ozan: I love that story. When we get that hard-hitting critical feedback, our tendency is to push back and say, “Well, you’re wrong. I’ve been working on this thing for two years—it’s got to be good!” But you took the feedback to heart and started from scratch, which is so hard to do.

And in a society that’s so obsessed with shortcuts and lifehacks, that story is a rare example of something that Ben Horowitz says: “There are no silver bullets, so we’ll have to use a lot of lead ones instead.” You used a lot of lead bullets over that seven-year period, and it paid off in spades.

Ready for more big ideas from Susan Cain? Join the Next Big Idea Club today!