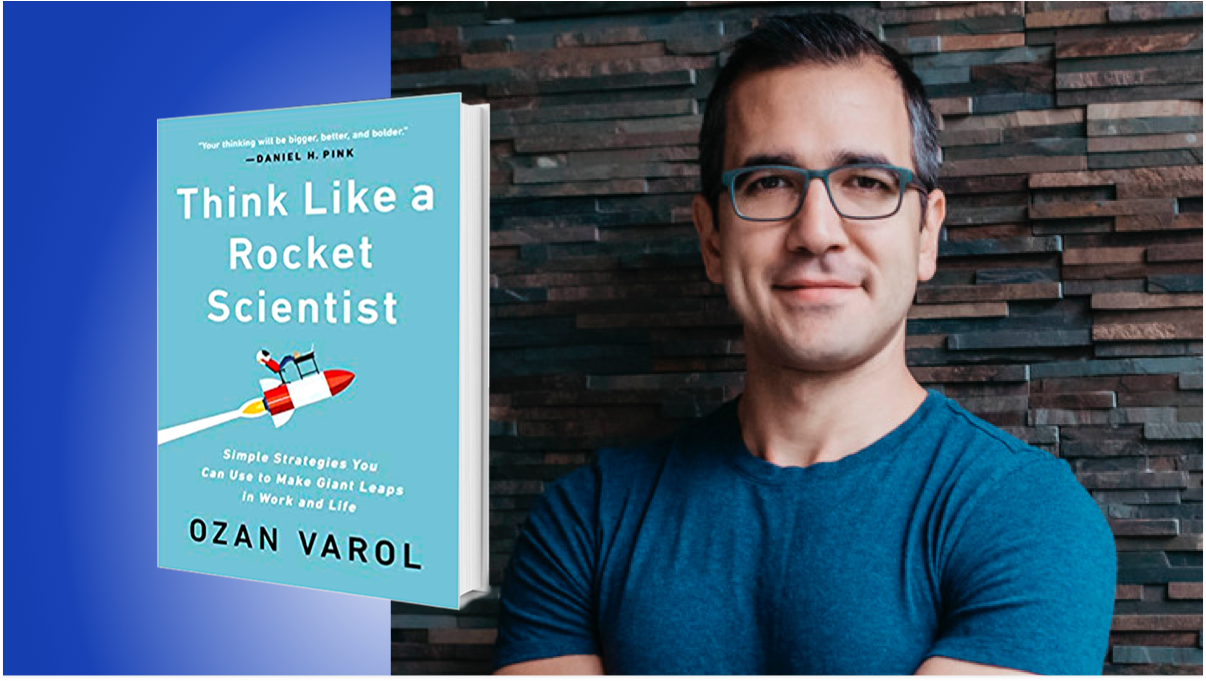

Ozan Varol is a rocket scientist turned award-winning law professor whose new book is Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life. He served on the operations team for the 2003 Mars Exploration Rovers project that sent two rovers to Mars, and his work has been featured in domestic and foreign media, including BBC, Time, CNN, Washington Post, Slate, and Foreign Policy.

Below, Ozan shares 5 key insights from Think Like a Rocket Scientist in this exclusive Next Big Idea Club Book Bite.

1. Reframe problems to generate better solutions.

In 1999, the Mars Polar Lander crashed on the Martian surface, and Ozan Varol’s team needed a new approach to landing on Mars before sending their own rover. But they stumbled on a new, game-changing question: “Can we send two rovers instead of one?” By focusing on the overall strategy (minimizing risk) rather than a specific tactic (fixing the landing gear), they discovered a solution hiding in plain sight. Indeed, breakthroughs often begin not with a smart answer, but with a smart question.

2. Utilize first principles thinking.

When Elon Musk was shopping for rockets, he was shocked—they were way too expensive, even for his budget. But then he had an epiphany: Maybe he could build his own. Sure enough, he discovered that buying the raw materials and building the rockets from scratch would cost about 2% of the price of a typical rocket. This is a great example of first principles thinking, which requires you to hack through existing assumptions and common practices until you’re left with just the fundamentals. Musk asked himself, “What is actually required to launch a rocket?” and moved forward from there.

3. Success is a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

When we succeed, we often assume that everything went according to plan, and we ignore the warning signs, the near misses, and the necessity for change. This is why the Challenger space shuttle exploded—there was a flaw in what are known as the “O-rings,” but the problem wasn’t new. NASA had succeeded in prior flights despite O-ring issues, and they became complacent. So remember that even successes contain opportunities for learning and improvement.

4. Don’t fail fast—learn fast.

The fail fast, fail often, fail forward mantra is all the rage these days in Silicon Valley. Failure is celebrated, viewed as a secret handshake shared by insiders. But regardless of what Silicon Valley tells you, failure sucks. And when we celebrate something, we don’t learn from it. Rocket scientists apply a more balanced approach to failure—they don’t celebrate it, but they also don’t let it get in their way. They know that failure can be the best teacher, and they recognize that breakthroughs are evolutionary, not revolutionary.

5. Prove yourself wrong.

In 1999, the Mars Climate Orbiter burned up in the Martian atmosphere. The problem? Lockheed Martin and JPL, who had teamed up for the project, assumed that all was well, and never realized that they were using different units of measurement. So instead of looking for reasons why your plan is working, look for evidence that it’s not—in other words, try to prove yourself wrong. In this way, you’ll resist deeply entrenched biases, and you’ll open yourself up to competing facts and arguments. The goal should be to find what’s right, not to be right.