One overcast morning in May 2014, Google Ventures design partner John Zeratsky walked into a drab beige building in Sunnyvale, Calif. John was there to talk with Savioke, one of Google Ventures’ newest investments. He wound his way through a labyrinth of corridors and up a short flight of stairs, found the plain wooden door marked 2B, and went inside.

Now, tech companies tend to be a little disappointing to those expecting glowing red computer eyes, Star Trek-style holodecks, or top-secret blueprints. Most of Silicon Valley is essentially a bunch of desks, computers, and coffee cups. But behind door 2B there were piles of circuit boards, plywood cutouts, and plastic armatures fresh off the 3-D printer. Soldering irons, drills, and blueprints. Yes, actual top-secret blueprints. “This place,” Zeratsky thought, “looks like a startup should look.”

Then he saw the machine. It was a 3.5-foot-tall cylinder, roughly the size and shape of a kitchen trash can. Its glossy white body had a flared base and an elegant taper. There was a small computer display affixed to the top, almost like a face. And the machine could move. It glided across the floor under its own power.

“This is the Relay robot,” said Steve Cousins, Savioke’s founder and CEO. Steve wore jeans and a dark T-shirt, and had the enthusiastic air of a middle-school science teacher. He watched the little machine with pride. “Built right here, from off-the-shelf parts.”

The Relay robot, Cousins explained, had been engineered for hotel delivery service. It could navigate autonomously, ride the elevator by itself, and carry items such as toothbrushes, towels, and snacks to guest rooms. As they watched, the little robot carefully drove around a desk chair, then stopped near an electrical outlet.

Savioke (pronounced “Savvy Oak”) had a team of world-class engineers and designers, most of them former employees of Willow Garage, a renowned private robotics research lab in Silicon Valley. They shared a vision for bringing robot helpers into humans’ everyday lives—in restaurants, hospitals, elder care facilities, and so on.

Cousins had decided to start with hotels because they were a relatively simple and unchanging environment with a persistent problem: “rush hour” peaks in the morning and evening when check-ins, check-outs, and room delivery requests flooded the front desk. It was the perfect opportunity for a robot to help. The next month, this robot—the first fully operational Relay—would go into service at a nearby hotel, making real deliveries to real guests. If a guest forgot a toothbrush or a razor, the robot would be there to help.

But there was one problem. Cousins and his team worried that guests might not like a delivery robot. Would it unnerve or even frighten them? The robot was a technological wonder, but Savioke wasn’t sure how the machine should behave around people.

There was too much of a risk, Cousins explained, that it could feel creepy to have a machine delivering towels. Savioke’s head designer, Adrian Canoso, had a range of ideas for making the Relay appear friendly, but the team had to make a lot of decisions before the robot would be ready for the public. How should the robot communicate with guests? How much personality was too much? “And then there’s the elevator,” Cousins said.

John nodded. “Personally, I find elevators awkward with other humans.”

Trending: How to Transform Daily Habits into Life-Changing Rituals

“Exactly.” Cousins gave the Relay a pat. “What happens when you throw a robot in the mix?”

Savioke had only been in business for a few months. They’d focused on getting the design and engineering right. They’d negotiated the pilot with Starwood, a hotel chain with hundreds of properties. But they still had big questions to answer. Mission-critical, make-or-break type questions, and only a few weeks to figure out the answers before the hotel pilot began.

It was the perfect time for a sprint.

The sprint is Google Ventures’s five-day process for answering crucial questions through prototyping and testing ideas with customers. It’s a “greatest hits” of business strategy, innovation, behavioral science, design, and more—packaged into a step-by-step process that any team can use.

The Savioke team considered dozens of ideas for their robot, then used structured decision-making to select the strongest solutions without groupthink. They built a realistic prototype in just one day. And for the final step of the sprint, they recruited target customers and set up a makeshift research lab at a nearby hotel.

Here’s a more detailed look at how the Savioke sprint went down.

First, the team cleared a full week on their calendars. From Monday to Friday, they canceled all meetings, set the “out of office” responders on their email, and completely focused on one question: How should their robot behave around humans?

Next, they manufactured a deadline. Savioke made arrangements with the hotel to run a live test on the Friday of their sprint week. Now the pressure was on. There were only four days to design and prototype a working solution.

On Monday, Savioke reviewed everything they knew about the problem. Cousins talked about the importance of guest satisfaction, which hotels measure and track religiously. If the Relay robot boosted satisfaction numbers during the pilot program, hotels would order more robots. But if that number stayed at, or fell, and the orders didn’t come in, their fledgling business would be in a precarious position.

Together, we created a map to identify the biggest risks. Think of this map as a story: guest meets robot, robot gives guest toothbrush, guest falls for robot. Along the way were critical moments when robot and guest might interact for the first time: in the lobby, in the elevator, in the hallway, and so on. So where should we spend our effort? With only five days in the sprint, you have to focus on a specific target. Cousins chose the moment of delivery. Get it right, and the guest is delighted. Get it wrong, and the front desk might spend all day answering questions from confused travelers.

One big concern came up again and again: The team worried about making the robot appear too smart. “We’re all spoiled by C-3PO and WALL-E,” explained Cousins. “We expect robots to have feelings and plans, hopes and dreams. Our robot is just not that sophisticated. If guests talk to it, it’s not going to talk back. And if we disappoint people, we’re sunk.”

On Tuesday, the team switched from problem to solutions. Instead of a raucous brainstorm, people sketched solutions on their own. And it wasn’t just the designers. Tessa Lau, the chief robot engineer, sketched. So did Izumi Yaskawa, the head of business development, and Cousins, the CEO.

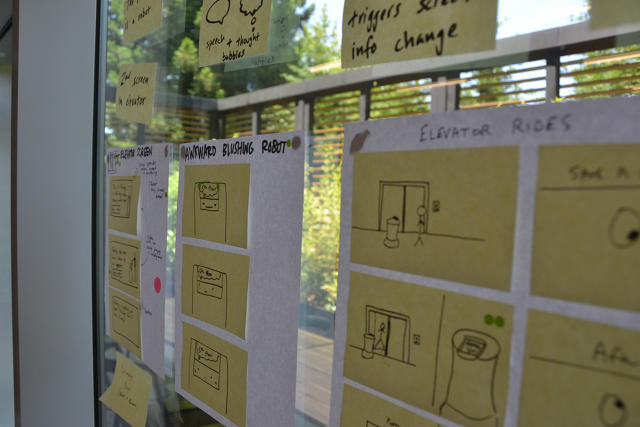

By Wednesday morning, sketches and notes plastered the walls of the conference room. Some of the ideas were new, but some were old ideas that had once been discarded or never thought through. In all, we had 23 competing solutions.

How could we narrow them down? In most organizations, it would take weeks of meetings and endless emails to decide. But we had a single day. Friday’s test was looming, and everybody could sense it. We used voting and structured discussion to decide quickly, quietly, and without argument.

The test would include a slate of Savioke designer Adrian Canoso’s boldest ideas: a face for the robot and a soundtrack of beeps and chimes. It would also include one of the more intriguing but controversial ideas from the sketches: When the robot was happy, it would do a dance. “I’m still nervous about giving it too much personality,” Cousins said. “But this is the time to take risks.”

Trending: 5 Reasons Life Gets Better After Your 40s

“After all,” said Lau, “if it blows up now, we can always dial back.” Then she saw the looks on our faces. “Figure of speech. Don’t worry, the robot can’t actually blow up.”

As Thursday dawned, we had just eight hours to get the prototype ready for Friday’s live test in the hotel. That shouldn’t have been enough time. We used two tricks to finish our prototype on time:

Much of the hard work had been done already. On Wednesday, we had agreed on which ideas to test, and documented each potential solution in detail. Only the execution remained.

The robot didn’t need to run autonomously, as it would eventually in the hotel. It just needed to appear to work in one narrow task: delivering one toothbrush to one room.

Lau and fellow engineer Allison Tse programmed and tuned the robot’s movements using a beat-up laptop and a PlayStation controller. Canoso put on a pair of massive headphones and orchestrated the sound effects. The “face” was mocked up on an iPad and mounted to the robot. By 5 p.m., the robot was ready.

For Friday’s test, Savioke had lined up interviews with guests at the local Starwood hotel in Cupertino, California. At 7 a.m. that morning, we rigged a makeshift research lab inside one of the hotel’s rooms by duct-taping a couple of webcams to the wall. And at 9:14 a.m., the first guest was beginning her interview.

The young woman studied the hotel room decor: light wood, neutral tones, a newish television. Nice and modern, but nothing unusual. So what was this interview all about?

Standing beside her was Michael Margolis, a research partner at Google Ventures. For now, Margolis wanted to keep the subject of the test a surprise. He had planned out the entire interview to answer certain questions for the Savioke team. Right now, he was trying to understand the woman’s travel habits, while encouraging her to react honestly when the robot appeared.

Margolis adjusted his glasses and asked a series of questions about her hotel routine. Where does she place her suitcase? When does she open it? And what would she do if she’d forgotten her toothbrush?

“I don’t know. Call the front desk, I suppose?”

Michael jotted notes on a clipboard. “Okay.” He pointed to the desk phone. “Go ahead and call.” She dialed. “No problem,” the receptionist said. “I’ll send up a toothbrush right away.”

As soon as the woman returned the receiver to its cradle, Margolis continued his questions. Did she always use the same suitcase? When was the last time she’d forgotten something on a trip?

Trending: 5 Simple Strategies for Persuading Anybody

Brrrring. The desk phone interrupted her. She picked up, and an automated message played: “Your toothbrush has arrived.”

Without thinking, the woman crossed the room, turned the handle, and opened the door. Back at headquarters, the sprint team members were gathered around a set of video displays, watching her reaction.

“Oh my god,” she said. “It’s a robot!”

The glossy hatch opened slowly. Inside was the toothbrush. The robot made a series of chimes and beeps as the woman confirmed delivery on its touch screen. When she gave the experience a five-star review, the little machine danced for joy by twisting back and forth.

“This is so cool,” she said. “If they start using this robot, I’ll stay here every time.” But it wasn’t what she said. It was the smile that we saw over the video stream. And it was what she didn’t do—no awkward pauses and no frustration as she dealt with the robot.

Watching the live video, we were nervous throughout that first interview. By the second and third, we were laughing and even cheering. Guest after guest responded the same way. They were enthusiastic when they first saw the robot. They had no trouble receiving their toothbrushes, confirming delivery on the touch screen, and sending the robot on its way. People wanted to call the robot back to make a second delivery, just so they could see it again. They even took selfies with the robot. But no one, not one person, tried to engage the robot in any conversation.

At the end of the day, green check marks filled our whiteboard. The risky robot personality—those blinking eyes, sound effects, and, yeah, even the “happy dance”—was a success. Prior to the sprint, Savioke had been nervous about overpromising the robot’s capability. Now they realized that giving the robot a winsome character might be the secret to boosting guest satisfaction.

Not every detail was perfect, of course. The touch screen was sluggish. The timing was off on some of the sound effects. One idea, to include games on the robot’s touch screen, didn’t appeal to guests at all.

These flaws meant reprioritizing some engineering work, but there was still time.

Three weeks later, the robot went into full-time service at the hotel. And the Relay was a hit. Stories about the charming robot appeared in the New York Times and the Washington Post, and Savioke racked up more than 1 billion media impressions in the first month. But, most important, guests loved it. By the end of the summer, Savioke had so many orders for new robots that they could hardly keep up with production.

For more, check out Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days.